The Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) is defined as the speed, measured in millimeters per hour (mm/h), at which red blood cells (erythrocytes) settle to the bottom of a tube containing a sample of whole blood. This straightforward test is frequently ordered in hematology to help identify and monitor increases in inflammatory activity within the body, which can arise from various conditions, including autoimmune disorders, infections, or malignancies. While the ESR does not pinpoint a specific disease, it serves as a valuable indicator when used alongside other diagnostic tests to assess whether there is heightened inflammation present. Its longstanding use in clinical practice is attributed to its reliability, simplicity, and affordability, making it a useful "sickness indicator" in routine medical evaluations.

Sedimentation as a diagnostic tool was first recognized in the late 18th century and refined for clinical use in the late 19th century. Since then, automated and semi-automated methods, as well as alternative technologies, have been developed to provide equivalent, yet faster, results.

The ESR is frequently ordered along with a complete blood count to give a comprehensive overview of the patient's overall health. As a result, recent advancements have focused on integrating ESR technology into hematology analyzers, allowing both FBC and ESR results to be obtained from the same device.

Historical Technology Principle/ Reference method.

The Westergren method for measuring ESR, established by the International Committee for Standardization in Hematology (ICSH), has provided consistent and reliable results for nearly a century. This method has enabled laboratories worldwide to maintain comparable reference values. Recognized as the gold standard for ESR measurement since 1973 by the ICSH, the Westergren method was reaffirmed as the benchmark in 2011 by both the ICSH and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), even after the introduction of automated ESR analyzers. (1)

The ESR test determines how quickly red blood cells (RBCs), or erythrocytes, settle to the bottom of a Westergren tube in a sample of whole blood. This settling process is known as sedimentation.

RBCs usually settle more quickly in individuals with inflammatory conditions such as infections, cancer, or autoimmune diseases. These conditions increase the amount of proteins in the blood, causing red blood cells to stick together, or clump, which makes them fall faster. When RBCs clump together, they form stacks resembling coins, known as rouleaux (singular: rouleau).

3 stages of sedimentation

The formation of rouleaux is possible because of the unique disc shape of RBCs. Their flat surfaces allow them to make contact and stick to one another.

Normally, the outer surfaces of RBCs carry negative charges, causing them to repel each other. Many plasma proteins are positively charged and can neutralize this negative surface charge, enabling the RBCs to form rouleaux. As plasma protein levels rise, such as during inflammation, rouleaux formation increases, and these aggregates settle more quickly than individual red blood cells. In the Westergren tube, rouleaux settle at a constant rate, resulting in a faster ESR. Thus, the ESR reflects a physical process rather than a single marker.

Rouleaux formation, and consequently the ESR, is influenced by the levels of immunoglobulins and acute phase proteins such as prothrombin, plasminogen, fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, alpha-1 antitrypsin, haptoglobin, and complement proteins, which are elevated in various inflammatory conditions. Acute-phase proteins (APPs) refer to about 30 different, chemically diverse plasma proteins whose production is regulated in response to infection and inflammation. These proteins are produced by the liver and are tightly controlled by the body following tissue damage or injury. APPs function as inhibitors or mediators of the inflammatory response.

Blood is typically drawn into a tube containing liquid 3.2% sodium citrate and then transferred to a measurement tube.

The Westergren method uses a long tube with a 2.5 cm internal diameter, marked in millimeters from 0 to 200. After one hour, the distance that red blood cells settle to the bottom is measured, leaving clear plasma at the top. (2)

Sedimentation can be assessed either visually or by using an automated reading device.

Several alternative methods exist, such as the Wintrobe method, which uses tubes that are 100 mm long with a narrower diameter, and the micro-ESR technique, which employs a finger-prick blood sample diluted with sodium citrate and drawn into a 7.5 cm capillary tube.

Manual method variations also include adjusting the measurement time, changing the dilution, or applying a temperature correction factor.

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is a non-specific marker of inflammation. It reflects increased plasma proteins, which speed up the settling of red blood cells.

Several factors can affect ESR, including female gender, pregnancy, and aging, all of which may raise the rate.

ESR is not sensitive or specific enough to be used as a general screening test, since high levels can occur in many conditions. Elevated ESR alone has limited value, and some patients with cancer, infection, or inflammatory disease may still have normal results. An increased ESR should prompt healthcare providers to consider possible underlying illness. (3)

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is a widely used

hematology test that helps detect and monitor increased inflammation in the body, which may arise from conditions such as autoimmune diseases, infections, or tumors. Although ESR is not specific to any single disease, it is typically used alongside other diagnostic tests to assess whether inflammatory activity is present.

The rate at which red blood cells settle (known as rouleaux formation) can be influenced by the levels of immunoglobulins and various acute-phase proteins (prothrombin, plasminogen, fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, alpha-1 antitrypsin, haptoglobin, and complement proteins) which are present in different inflammatory conditions.

As mentioned earlier, malignancy can cause an elevated ESR. Inflammation plays a key role in cancer progression, so ESR may help predict risk and outcomes in cancer patients.

In a retrospective study using a Cox proportional hazards model, Choi et al. found that ESR was a significant predictor of cancer-specific survival in patients with the clear cell variant of renal cell carcinoma. (4)

A high erythrocyte sedimentation rate is also linked to metastasis and a poorer prognosis in patients with cutaneous malignant melanoma. Elevated ESR has been associated with an overall worse prognosis in several cancers, including breast, prostate, colorectal, Hodgkin disease, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (3), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. (5)

ESR is a valuable tool in evaluating children who present with an unexplained limp or difficulty bearing weight, as it helps differentiate septic arthritis from reactive arthritis.

When a joint effusion is detected, a normal ESR (0–20 mm/h) tends to support a diagnosis of reactive arthritis, a generally benign condition that often requires minimal intervention, rather than septic arthritis, and may reduce the need for additional procedures.

While a slightly elevated ESR may not be particularly useful for distinguishing between these conditions, a markedly elevated ESR (>40 mm/h) can provide important diagnostic insight. For example, in one study of pediatric patients assessed for septic hip arthritis, only 44% of those with septic arthritis had an ESR less than 40 mm/h, compared with 86% of patients diagnosed with transient synovitis. (6)

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a long-term autoimmune condition characterized by chronic inflammation, which can lead to joint pain, disability, and eventual joint damage. Patients with RA require ongoing monitoring to track disease progression and evaluate how well treatments are working.

One of the most widely used tools for monitoring RA is the Disease Activity Score based on 28 joints and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR). This assessment considers the condition of 28 specific joints in the body together with the patient’s ESR value to determine the level of disease activity. (7)

Some healthcare providers and research studies may also include C-reactive protein (CRP) measurements as part of their assessment, but the DAS28-ESR remains a standard method used internationally to monitor patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

An elevated ESR is recognized as a marker for Temporal Arteritis (Giant Cell Arteritis), which often presents acutely with severe temporal headache. Prompt treatment is critical to prevent complications like blindness. C-reactive protein (CRP) is another useful marker for rapid diagnosis.

In an eight-year study by Kermani et al., (8) examining the utility of ESR and CRP for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis, the sensitivity of CRP (86.9%) was slightly higher than ESR (84.1%) for patients confirmed by temporal artery biopsy.

The study established an ESR cut-off of 53 mm/hr for Giant Cell Arteritis. While CRP was more sensitive, using both elevated ESR and CRP improved diagnostic specificity compared to either test alone.

Although the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) lacks specificity and newer inflammatory biomarkers are available, it remains a key tool for diagnosing and monitoring disease. Its continued use is supported by its simplicity, affordability, and a substantial body of recent research.

Several automated or semi-automated techniques offer safer, faster, and more accurate results. The International Council for Standardization in Hematology (ICSH) has reviewed these methods and provided validation guidelines (9). Automated systems often estimate ESR by analyzing early red blood cell aggregation rather than measuring sedimentation directly.

The Working Group classifies ESR measurement approaches into three categories:

The Yumizen H500E and Yumizen H550E are CBC/differential analyzers equipped to measure ESR using CoRA (Correlated Rouleaux Analysis) technology, which delivers stable ESR results closely aligned with the Westergren method.

This “alternate” method evaluates the initial stage of ESR, the formation of rouleaux, and extrapolates the findings to provide an equivalent mm/h value.

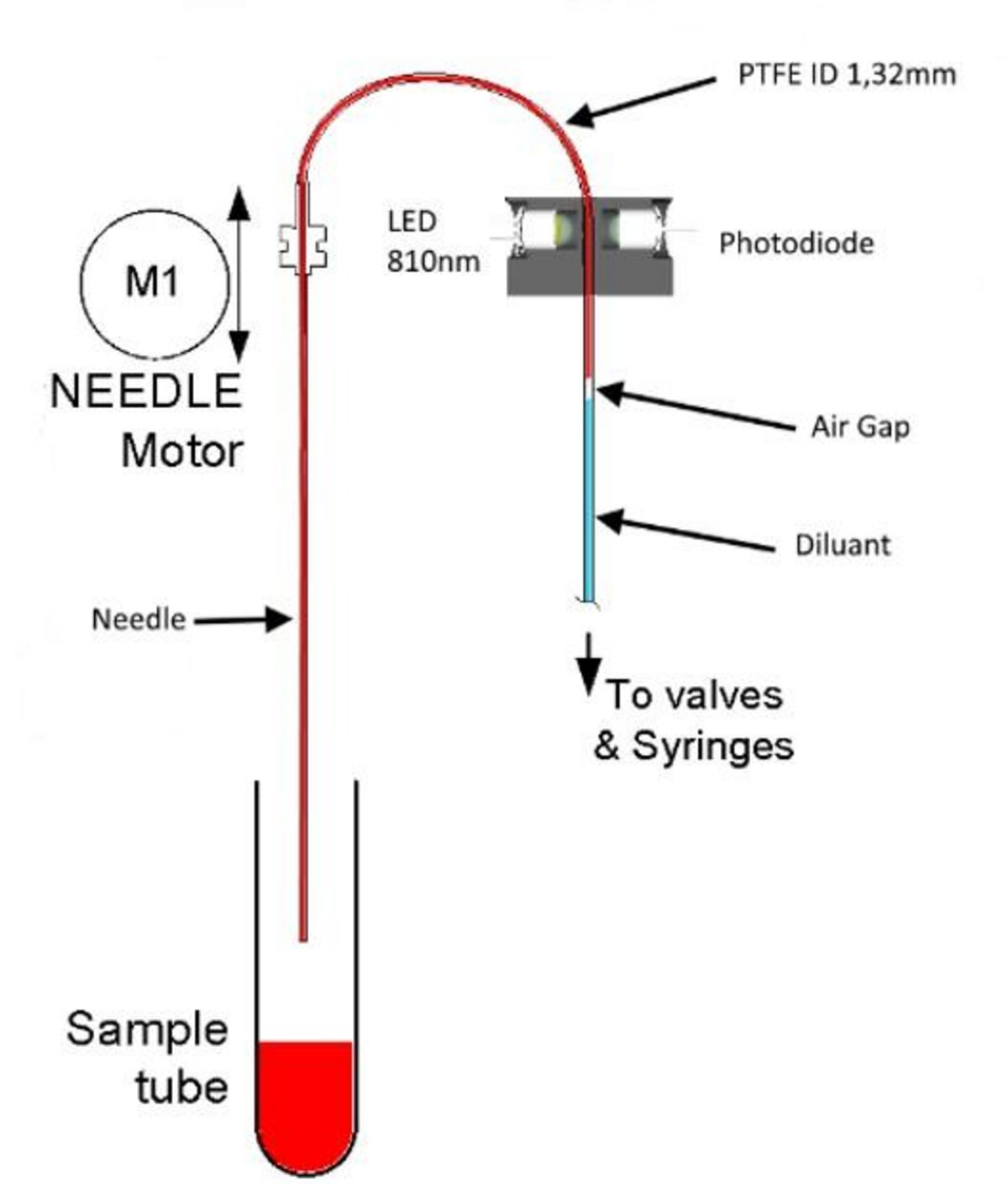

Measurements are captured every 50 microseconds by tracking near infrared light transmission through a capillary tube.

Stage 1: Aspiration – The aspiration tubing contains diluent (for a blank reading), air (to create a barrier), and whole blood. As blood is drawn, the resulting shearing forces deform the red cells. This “stretching” slightly reduces the cells’ ability to absorb light. The aspiration speed is designed to mimic human circulation, promoting appropriate red cell deformability without causing excessive stress that could alter normal cell behavior.

Stage 2: Relaxation – Aspiration pauses, allowing the red cells to return to their original shape, which alters the sample’s optical absorption.

Stage 3: Agglomeration – Over 30 seconds, red cells are permitted to aggregate, forming rouleaux (stacks or rolls of cells). As rouleaux develop, interstitial spaces increase, allowing greater light transmission. All changes in light transmission are tracked throughout, including blank measurements from the diluent.

A syllectogram is generated, and these values are used to calculate the ESR result, accounting for temperature and natural variations between samples. Each analyzer verifies correlation with the Westergren method as part of the production process.

Evolution of RBC agglomeration

CoRA ESR technology is available on three instruments: Yumizen H500E Open Tube, Yumizen H500E Closed Tube, and the autoloading Yumizen H550E, which can load and process up to four racks of ten tubes automatically.

Integrating CBC/differential and ESR in a single analyzer provides a broader testing panel when inflammation or infection is suspected, while also conserving laboratory space for routine hematology testing.

Results

Correlation vs Westergren method

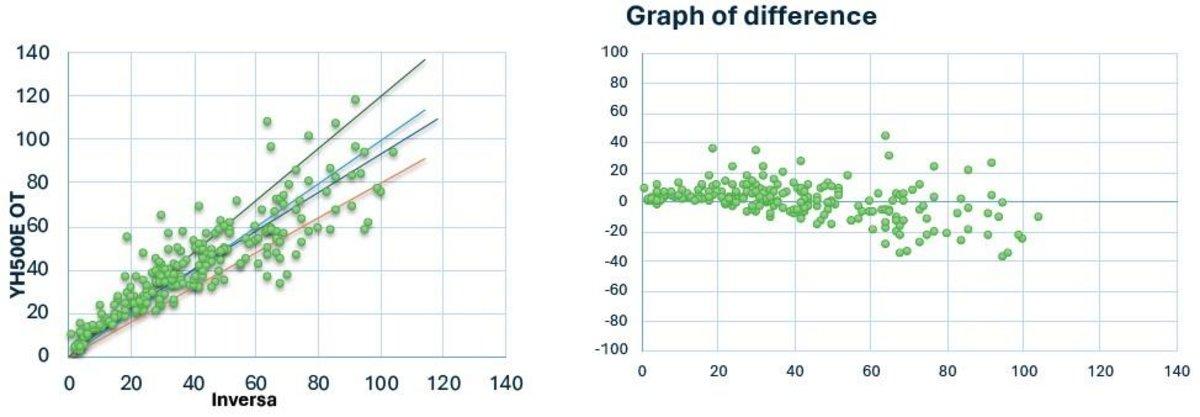

Yumizen H500E Open Tube (OT) vs Inversa

N = 226

Y = 0.889 x +4.78

R = 0.878

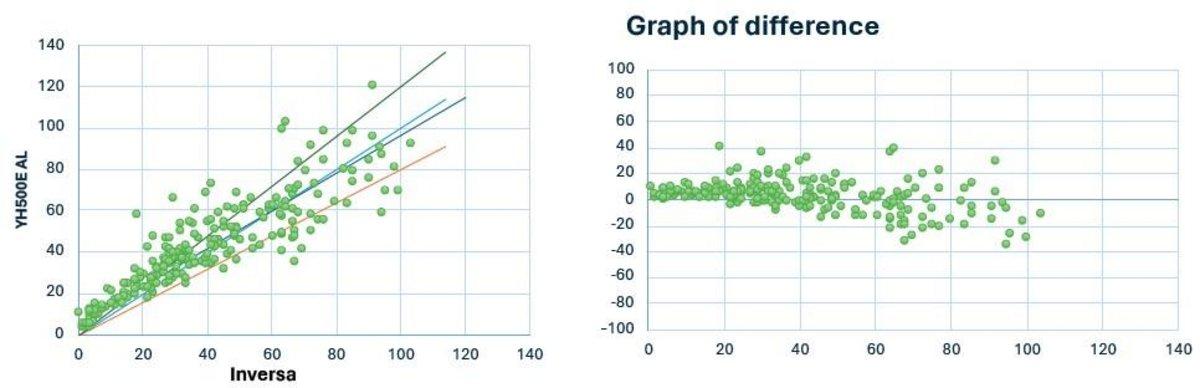

Yumizen H550E Auto Loader (AL) vs Inversa

N = 225

Y = 0.883 x +4.97

R = 0.883

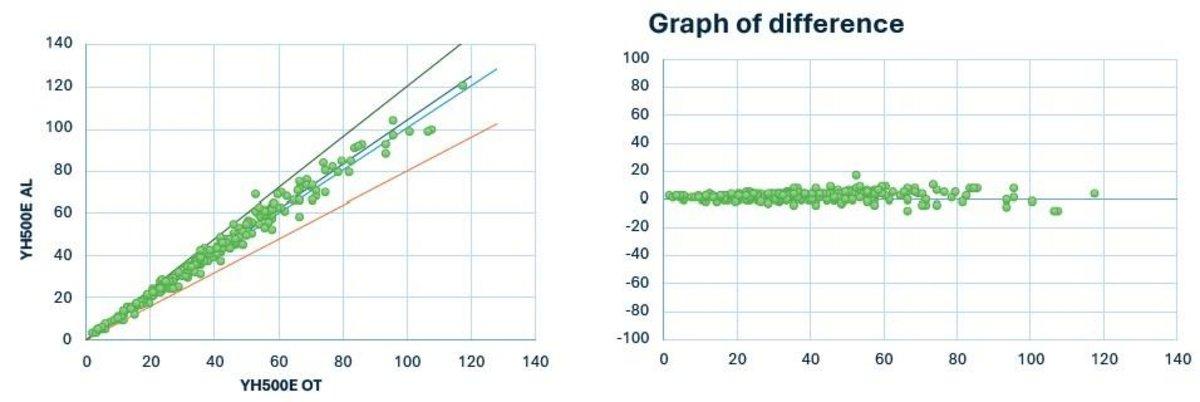

Inter-instrument correlation

Yumizen H550E Auto Loader (AL) vs Yumizen H500E Open Tube (OT)

N = 227

Y = 1.042 x -0.04

R = 0.99

K2 EDTA vs K3 EDTA

The K2 EDTA vs K3 EDTA correlation on the Yumizen H500E OT and the Yumizen H550E were R = 0.995, y= 1.053 x -0.26 and R = 0.996, y=1.0 x 0 respectively. It can therefore be concluded that there is no statistical difference between blood taken into the two types of anticoagulant.

Correlation vs Test 1 (alternative method ESR)

The correlation data showed a calibration bias between the two instruments. The application of a calibration factor between the two instruments could be used to provide corrected correlation analysis. The data from both Yumizen analyzers showed almost identical results so only the graphical data from the Yumizen H500E is shown below.

Yumizen H500E OT vs Test 1 After recalibration

N = 182

Y = 0.952 x +3.86

R = 0.897

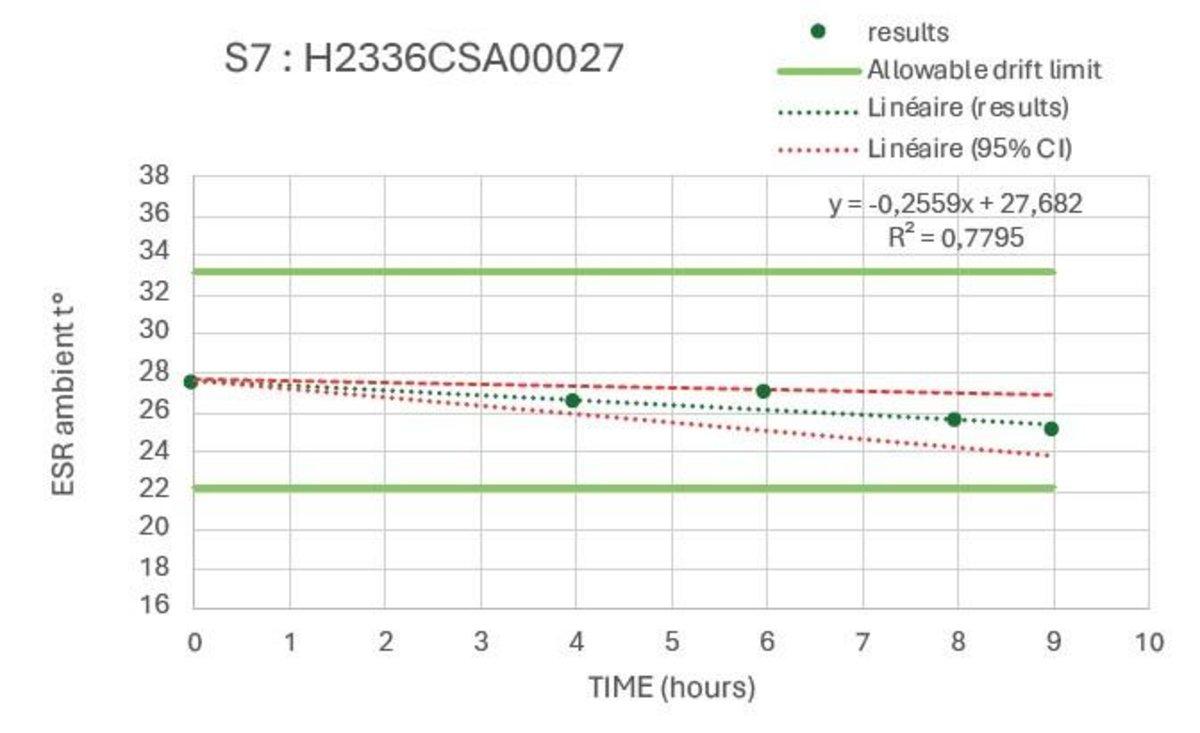

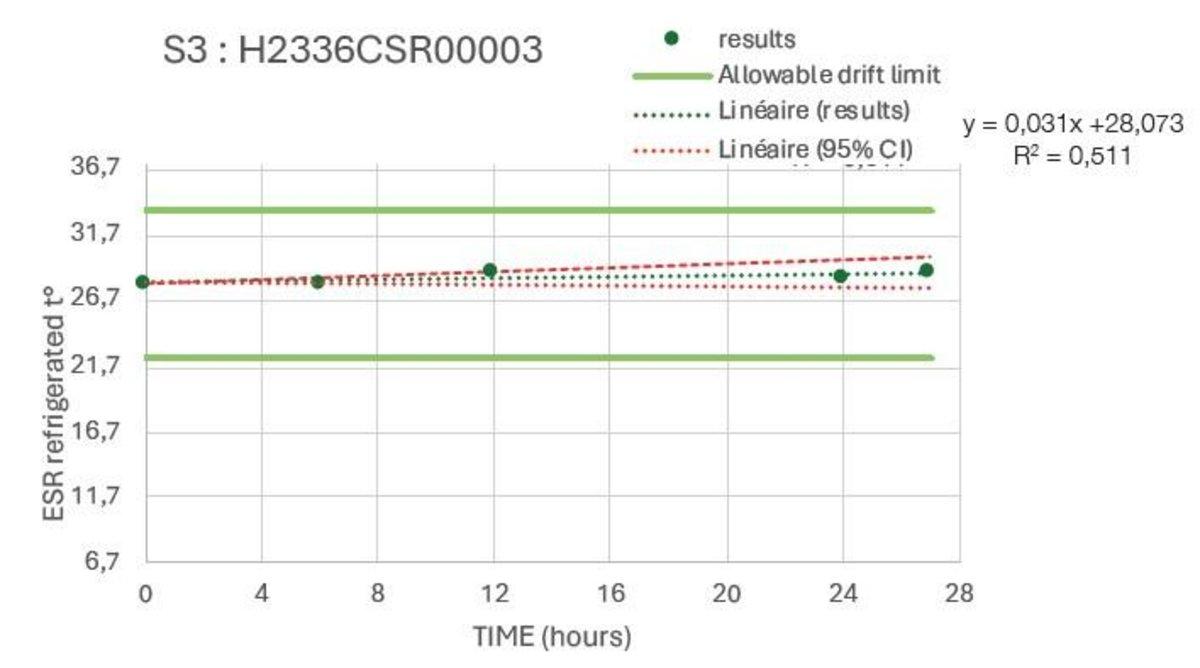

Sample Stability

The stability studies were carried out on multiple tubes with results spread across the analysis range. These confirmed a stability of >8hr at ambient temperature and >24hours refrigerated.

Example Ambient

Example Refrigerated

Do you have any questions or requests? Use this form to contact our specialists.